July 8, 2025

Resilient Power in the Wake of Hurricane Helene

By Olivia Tym

Credit: Olivia Tym, Clean Energy Group

One of the things I cherish most about Western North Carolina is its patchwork of small, close-knit communities nestled among mountains and valleys, all interconnected by an endless web of creeks and streams. Many of these communities are rural and secluded, a contrast to the region’s population center of Asheville, where I live. Although beautiful and unique, the geography of the region made it especially difficult to coordinate a regional response after the devastation wrought by Hurricane Helene on September 27, 2024.

Helene brought unprecedented rainfall and strong winds to the area. Water settled in the many low points, causing creeks and rivers to rise quickly. The resulting flood devasted Asheville and neighboring communities – many homes and businesses were under water and over 396,000 people in the state, mostly those in the Western region, lost power. Thousands were still without power over two weeks after the storm.

When Hurricane Helene moved inland, the town of Hot Springs, like the rest of the region, lost power. However, unlike Asheville, Hot Springs is equipped with a microgrid. On the Monday after the storm, the Department of Transportation allowed Duke Energy to cross the French Broad River bridge to get into Hot Springs, and in the following days they worked to address some minor microgrid issues including depleted batteries. While the microgrid was able to support load on Tuesday, October 1st, damage assessments were still being performed in the town and once flooded areas were deemed safe enough to reenergize, the microgrid returned power to the town’s critical facilities on October 2nd. This effort took just a few days- a rapid turnaround in comparison to many communities in the Carolinas and Georgia that faced weeks long outages. The microgrid continued to power Hot Springs for nearly a week before a mobile substation—a portable, self-contained electrical distribution system—was brought in to re-connect the town to the larger utility grid.

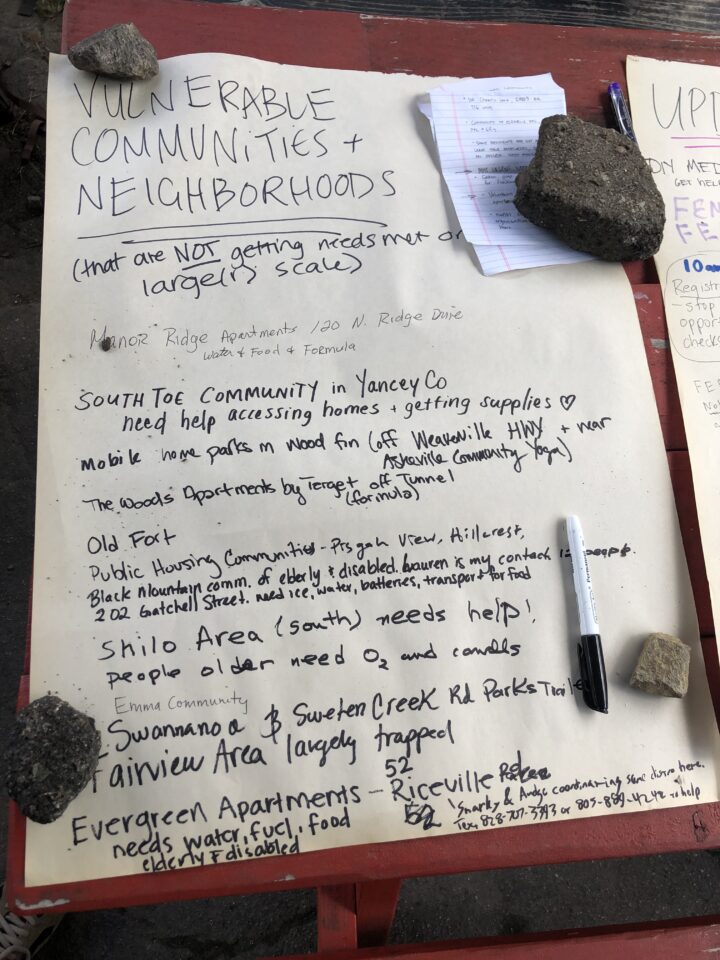

Other relief efforts were cropping up across Western North Carolina. In the immediate aftermath of the storm, after clearing a path through downed trees out of his East Asheville home, Jamie Trowbridge scrawled a handwritten note on the door of Sundance Power Systems, a solar installation company in Weaverville, NC, relaying the need for backup power to help residents gathering at the Barnardsville fire station and community center. Barnardsville, a rural community located 20 miles north of Asheville, was isolated, leaving many residents unable to access critical services.

Trowbridge worked to gather supplies stored in local garages and basements of his solar industry friends, and he started spreading the word about the need for donated batteries and solar gear. Coordinating this effort was challenging due to the lack of cell service across the region. Trowbridge had to drive to the top of a large hill in West Asheville just to get reception. I did the same in the aftermath of Helene, biking to higher elevation so that I could call family and let them know that I was safe.

Photo taken September 30, 2024.

Credit: Olivia Tym, Clean Energy Group

Word of Trowbridge’s efforts soon spread to Footprint Project, a nonprofit organization that provides emergency support through resilient power technologies to communities in the wake of natural disasters. Footprint arrived in Barnardsville with two mobile solar and battery storage trailers, which powered essential community facilities and provided a Starlink internet connection.

Once grid power was restored to Barnardsville, Footprint Project staff began identifying other communities in need of support. They established their base of operations and accumulated a large supply of solar and battery storage equipment. These donations became the foundation of Asheville-based Free Store, which provides long-term, no-cost rentals of solar and storage equipment to businesses, organizations, and individuals who are still in need of reliable power even many months after the storm. Firestorm Books, a West Asheville bookstore that became an impromptu neighborhood relief hub in the days after the storm, was powered through Free Store equipment. My friends and I met there daily to attend community meetings and to share food, resources, and plans.

Disaster relief efforts are still ongoing in Western North Carolina and there is still significant need for equipment as well as for future resilience planning. Matt Abele, Executive Director of the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association (NCSEA), emphasized that in the immediate aftermath of a disaster there is often an outpouring of support, but in the months that follow, impacted areas often see a significant slow-down in this support. “There is a real opportunity in this moment to ensure we are elevating the value that this equipment has already brought to the region, and how it can help the region better prepare for future storms,” Abele said.

Local organizations are working to maintain this momentum while also still recovering from the disaster. Electrify Asheville-Buncombe is advocating for solar and battery storage to power wells for drinking water in rural areas. NCSEA, in partnership with Greentech Renewables, and Land of Sky Regional Council are engaged in an ongoing fundraising campaign to support fully mobile equipment (with a particular emphasis on serving vulnerable populations such as those with electricity-dependent medical needs), semi-permanent installations, and permanent community resilience hub infrastructure located in population-dense areas where people can aggregate after disasters. NCSEA also advocates for more state grant funding for microgrids serving critical facilities such as telecommunications and water infrastructure. Fundraising efforts benefitting more mobile solar+storage equipment, facilitated through Footprint Project, also continue in the region. Using the Hot Springs microgrid as a case study, Duke Energy is establishing plans to expand microgrid deployment in the region, specifically aimed at bolstering electricity resilience in rural areas with a history of prolonged outages.

Credit: Olivia Tym, Clean Energy Group

The organizations, communities, and utilities operating in Western North Carolina continue to work tirelessly to repair the damage and rebuild what was lost. This is evidenced by the slow cleanup progress I see every time I drive along the French Broad River or hear news of roads and bridges being re-opened. These ongoing efforts go beyond simple restoration; they represent a critical opportunity to reimagine and reinforce the region’s infrastructure, economy, and support systems. By integrating more sustainable practices, enhancing emergency preparedness, and fostering stronger community networks, these initiatives not only address the immediate aftermath but also are laying the groundwork for a more resilient and adaptive region that is better equipped to withstand future challenges. Solar and battery storage needs to be a critical piece of that plan.

To learn more about Western North Carolina’s response to Hurricane Helene and about future resilience planning for the region, watch Clean Energy Group’s recorded webinar with speakers from Duke Energy, Footprint Project, and the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association.

This blog was originally published on Solar Power World.